Kate and her aunt Rosa against the backdrop of the Monarch forests.

In February, Design Wild’s Project Manager, Kate, embarked on a pilgrimage to see the overwintering site of the Monarch butterflies in Michoacán, Mexico. The story of the monarchs is as rich as the orange of their wings. They unwittingly model, for those who listen, some of the qualities we’d love to see manifest in our future world. For us at Design Wild, the efforts made to protect them also speak of the inextricable nature of building justice for both humans and the living companions around us.

This age old migration begins (and ends, and continues) in what we think of as the Northeast United States and Canada. During the spring and summer months, monarchs lay eggs on the milkweed plant, Asclepius. Milkweed is a proud and beautiful plant, but unfortunately, it is often misrepresented as a weed. Once born on milkweed, our baby caterpillars eat their way through childhood. Monarch caterpillars grow up to 2,7000 times their starting weight in just two weeks. When the time comes, these mighty caterpillars spin themselves into royal emerald green cocoons, embellished with gold dots. After a couple of weeks, they complete their metamorphosis, emerging as the regal and striking orange and black butterflies.

Mighty milkweed going to seed

Royal chrysalis

Several generations of monarchs are born in spring and summer. They typically live for 3-6 weeks, enough time to eat, mate, and lay eggs, bringing new generations into the world. But come fall, the emerging monarch generation starts its long journey south.

This special generation of monarchs, known as the ‘supergeneration,’ has the age-defying power to live up to eight months. They manage this by remaining in a state of elongated adolescence, trading in maturity for the strength to migrate.

But we still haven’t figured out how this generation knows to preserve its strength or begin its migration.

Another mysterious power monarchs hold is that year after year, the millions of butterflies, though new to the world as individuals, follow their millennia-old instinct to find the exact same forests in the high forests of Michoacán, Mexico. Not only do they find the same Sacred Fir, or Oyamel forests, they flock to a relatively small selection of the trees, cloaking their branches with their tired bodies. While most migrations in nature occur when a generation of animals or insects travels to the same place annually.

The miracle of the monarchs is that a generation that flies south is not the same one that returns the next year. Instead, it’s their great, great, great, great grandchildren who are embedded with the ancestral instinct to find the very same forests.

Upon reaching the Sacred Fir trees the monarchs rest from mid-November to Mid-March. They eat, pollinate the wildflowers that line the forest floors, sip water from plants and nearby streams, and sacrifice some of their bodies to the birds that also inhabit the forests. In March, they begin their journey north. This time, they stop in Texas and other Southern waystations to lay eggs. Now the supergeneration monarchs have used the last of their strength and move on to the next life. But they pass their instinctual sense of home to their young who continue northward to find their breeding grounds.

And so it continues, the journey of the monarchs, one of the natural miracles that eludes us humans. What can we learn from this story?

1. We can draw strength from their own story of persistence that carries a small, seemingly fragile insect over three thousand miles. How desperately we need that level of endurance and determination right now to get through dark times. How do we preserve strength? Can we too stave off the exhausting effects of aging into a jaded adult? Young people who’ve spearheaded movements like the One Mind Youth Movement at Standing Rock, the youth involved in bringing Black Live Matter to the national stage, and the recent Parkland student movement against gun violence show us the power of youthful energy and perseverance.

2. The monarchs also embody the lesson of unity. Alone, each butterfly weighs just half of one gram, susceptible to the winds, rain, cold and predators that they inevitably encounter along their journey. Yet when they fly among millions, they are strong, they become one migration, one movement. Nature knows the protection that comes with a shared purpose, coordinated movement, and deep instinctual and ancestral guidance. We too must move as one migration, transitioning ourselves together to the future we want to inhabit.

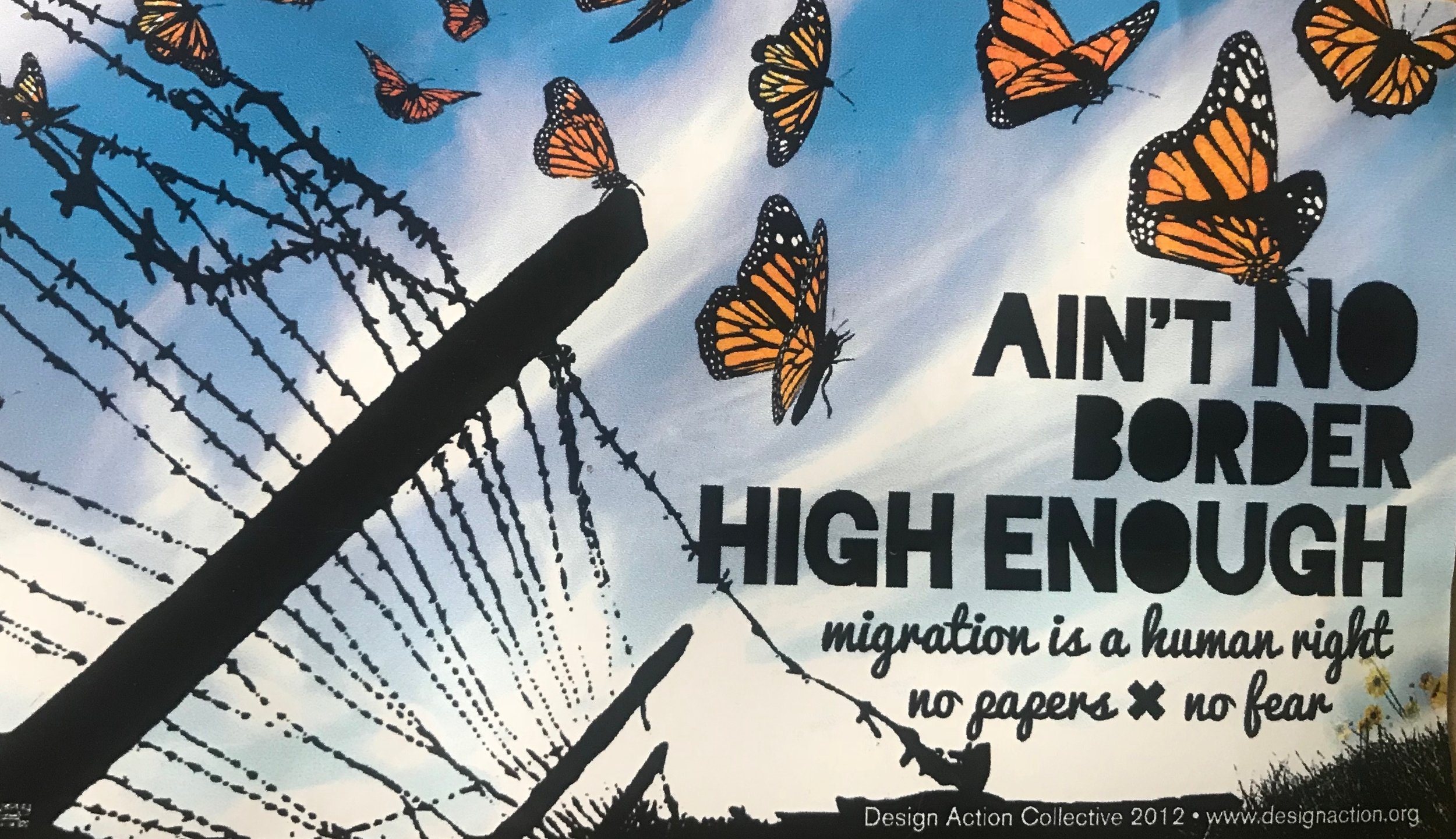

3. It also struck me that the monarchs exist in a borderless world, where butterflies are free to make home in many places. How radically different this country and world could be if we honored the same migrations for people – immigrants, refugees, Dreamers – and appreciated the bravery and strength of those who travel by choice or out of need to make new homes.

How ludicrous the idea of a wall seemed upon seeing these tiny creatures so gracefully inhabit the Oyamel Forests. Migrations are woven into the fabric of nature.

We acknowledge that many human migrations are forced; but the lesson remains, how can we honor the journey that immigrants have made? Let us make it safer to relocate, recognize the beauty and contributions those who travel, and respect the notion that living things naturally inhabit multiple homes. We can study these butterflies that have learned to become native to many places. Powerful humans have created laws and borders and repressive institutions like ICE – but climate change has already and will continue to force huge populations of people to leave their homes so let’s imagine a future where we recreate such forces to reflect the natural law of migrations.

4. From the monarchs, we also can reflect on the need for new forms of stewardship and environmental justice. Widespread degradation of the monarch’s northern breeding and southern overwintering habitats has been a major threat to monarch populations. In the northeast, the use of pesticides and insecticides, mowing down milkweed in roadsides and pastures, ozone pollution, suburbanization and sprawl are all contributing to vast decreases in the treasured milkweed plant so essential to monarch breeding. In the forests of Mexico, illegal logging, forest fires, and poor tourist management have been responsible for the loss of hundreds of hectares of forest habitat where monarchs spend their winters. Butterflies rely on the thick blanket of the Oyamel canopies to keep out the cold winds and regulate temperatures. When trees in the forests are cut, it alters the fragile balance of temperatures, causing swings that kill the butterflies by freezing or overheating.

But the story of conservation efforts in Mexico demands attention, as it is not a simple act of ‘protecting’ forests. The Oyamel forests in Michoacán are owned by private landowners and by ejidos. Ejidos are a structure of communal land ownership that formed after the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century as a way to redistribute rural land from a small number of elites to groups of poor campesinos. Many of the ejidos of the forests are comprised of indigenous people. Despite their landholdings, many of the communities surrounding the Monarch forests remain some of the poorest in Mexico.

And as with many natural areas, when the government and scientists “discovered” the migrating monarch havens in the 1980s, these forests were of course already inhabited by the ejido communities. The people of these forests have been cutting trees in the forests for years in order to clear space for farming and for logging, which for a long time have been their own economic options.

So after the 1986 presidential decree that the forests become protected, the communities using the forests grew angry and resentful that their economic livelihoods were suddenly deemed illegal, with no opportunities for dialogue or input. A government who for years neglected to address the needs of poor communities was suddenly protecting butterflies without any acknowledgement of the impact? After years of conflict, burning forests, and increased illegal logging, the government re-strategized, this time holding conversations with the ejidos and landowners of the forest. In 2000 the protected area increased, but this time a fund was started to pay communities compensation for the income they were losing by not logging.

The tension over the forests continues today, reflecting a complicated but familiar history of colonialism, the struggle for indigenous land rights, and economic injustice. The story of the monarchs is thus tied up with the story of the forest dwellers. We can’t protect one without taking into account the other, though our capitalist system would have us pit people against planet. [see this story for more on the struggle for sustainable tourism].

But against the backdrop of a daunting global exploitative economic system, there is hope.

The ejidos that own land in the monarch sanctuary forest that Kate visited, el Rosario, have embraced the monarchs and become, once again, protectors of the forests.

The entrance to El Rosario Reserve

Surely these ejidos still struggle economically, relying on a volatile tourism industry that has been hard-hit by the drug violence plaguing Michoacán. Many residents have had to leave to find work in cities and the United States. But can we honor these community-led efforts to combat the narrative that we have to choose between people and planet?

Can we continue to support the work of strong local communities who forgo the temptation to cut the trees to instead find enterprises that regenerate and respect the monarchs and their home?

These members of the Ejidos are the guardians of the monarchs. If you look closely on the ground, you can see hundreds of monarchs fluttering their wings, trying to warm up.

Up in the north, we’ve also seen movements to replant milkweed and other pollinator habitats. Loving humans are creating monarch waystations in backyards, public spaces, and school gardens. Even the five-year-olds that Kate teaches in a Brooklyn elementary school now share in the delight of planting milkweed so that our black and orange friends have homes to lay eggs. Certainly we need a structural change to transform the industrial farming practices that are causing the milkweed decline. But let’s also find hope in the grassroots efforts to educate people and create alternatives in the long-term struggle.

Ten years ago, the monarch population was facing an epic decline. The population dropped from covering 18 hectares of forests in 1996 to covering just .67 hectares in 2013. But since 2016, it has gone up slightly, covering about 4 hectares. Though still at risk of volatile temperature swings caused by global climate change, some are finding hope in the cross-national efforts to protect and rebuild habitat, and find alternative economic options for the people living in the monarch forest reserves.

Each branch of the Oyamel tree is cloaked with thousands of monarchs, turning from grey to orange as the sun emerges.

We have to remember that the fate of the people in the Oyamel forests, the fate of the children learning to steward habitats in the northeast United States, the fate of the workers on the farms that are forced to use unhealthy chemicals that kill milkweed, and the fate of the monarch butterflies are all wrapped up in one. Let us rethink the traditional conservation lens that has so often ignored the plight of the marginalized.

At last, the final reflection on the power of the monarchs came viscerally as Kate ascended to the top of the mountain in search of the chosen Oyamel trees. The hundreds of people surrounding her fell to a hush, as if they were in a museum, a collective humility that comes from watching millions of beautiful creatures launch from their branches and fill the sky as the sun warms them, pulsing the forest with orange.

How lucky we are to be visitors on this earth, witness to ancient wonder – the butterflies and their fir trees have been around far longer than we can fathom – it’s a reminder to listen.

Monarchs launch into flight when the sun warms the Oyamel forest of El Rosario Sanctuary.